Some Final Thoughts

A few years ago in San Francisco two film students working on a video project stopped and asked me: “What is it like being a Filipino-American today?” I stood silent, not knowing how to answer. I was confused, only knowing what it’s like being “American,” and only using “Filipino” when describing my ethnicity and the food my family ate. I felt guilty for not having the words to reply pridefully. Today, I understand my puzzlement. It only took a third trip, an intense month, and an outsider’s perspective to get there (thank you Alex.) So, I would be remiss not to offer some final thoughts, along with graphics and numbers (for you Mui!). It is my motherland, after all.

The United States has been idealized by the Philippines for a very long time, and continues to be so today. Because the Western influence is so strong and the colonial mentality still exists (it’s the only Asian country that was colonized by the US), even the young generation does not have a full grasp of their own Filipino history and identity. As an American-born Filipino, where does that leave me? I had been immediately assimilated into American culture. I only knew José Rizal by name until a few months ago, and he is the brilliant national hero! Our identity crisis is a real thing! We are an invisible minority. I can write more about this, but E. J. R. David does it better.

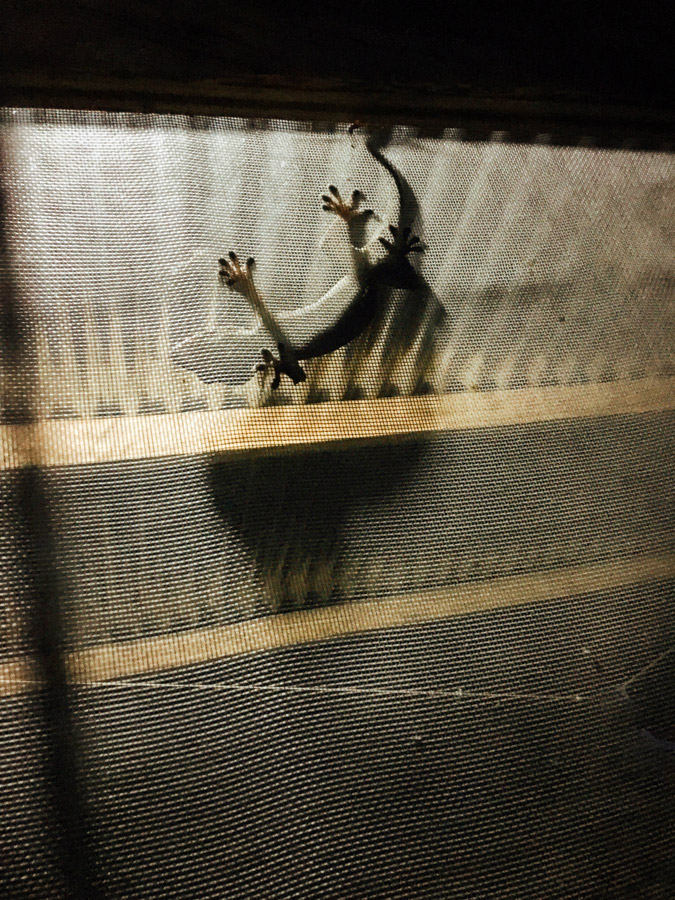

Anyway, after our time in the Philippines, I realized, for me, that being Filipino-American simply means to be from “a nation of giving, tolerance, hospitality” and resilience. I identify with the way of life I know, taught to me by my parents — to be kind and respectful, to care for each other, to give back, to make sure there is more than enough to eat, and most importantly, that everyone is an uncle, auntie, or cousin. Because that’s not confusing at all.

And now, for some fun numbers...

Numbers from the Philippines

- Days in the Philippines: 25 days

- Our daily average cost for lodging and food per person: 900 PHP ≈ $19.50

- Cost of a 4L water: 75 PHP ≈ $1.50

- Cost of a medium latte: 100 PHP ≈ $2.25

- Cost of scuba diving: 3,500 PHP ≈ $75.00 for a three tank dive

- Cost of island hopping: 1,050 PHP ≈ $23.00 for a full day

- Cost of renting a scooter: 500 PHP ≈ $10.75 for 24 hours

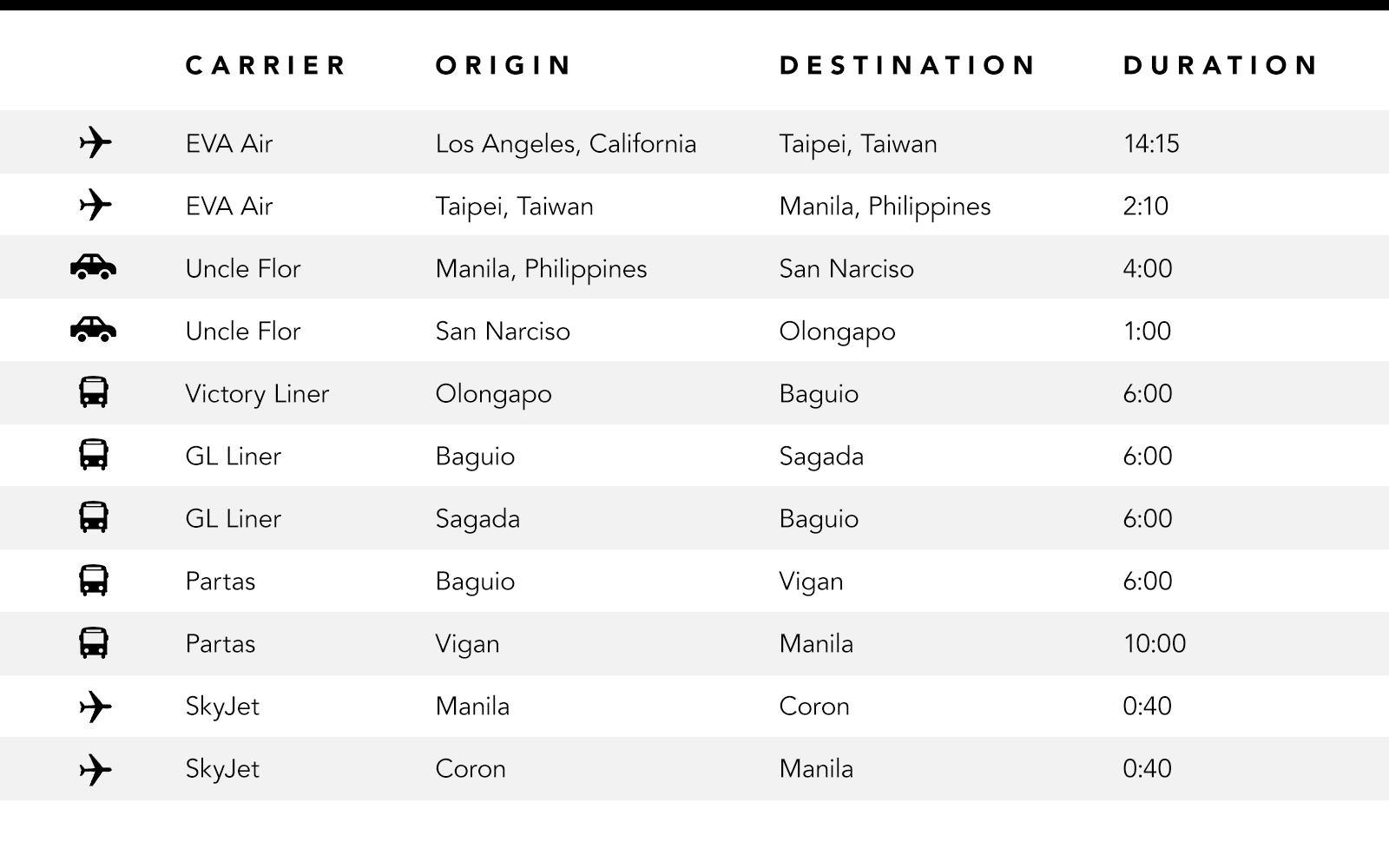

- Total time on an airplane: 17 hours and 45 minutes

- Total time on a bus: 34 hours

- Total time on a boat: 16 hours